Key Findings

- EU aerial assets are deployed to detect migrant boats from the air and guide the so-called Libyan Coast Guard to the locations of escaping boats.

- Aerial surveillance has led to the capture of tens of thousands of people and their return to the Libyan war zone.

- Through both aerial surveillance and coordination activities in migrant interceptions, EU actors have violated their SAR obligations and facilitated interception activities of the Libyan authorities. EU actors are thus complicit in the systematic violation of human rights.

Executive Summary

Over recent years, the EU and its Member States have progressively reduced Search and Rescue (SAR) activities performed by their institutional actors, such as Coast Guards, Maritime Rescue Coordination Centers (MRCCs) and military missions, i.e. EUNAVFOR MED. Instead, the EU has (re)-built the so-called Libyan Coast Guards (scLYCG) by financing, equipping, training and politically legitimizing them. These efforts culminated in June 2018 with the notification to the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) of a new SAR region to be coordinated by the Libyan authorities. At the same time, NGOs carrying out vital SAR operations have been criminalised and de-legitimised.

Despite the fact that the scLYCG is effectively a militia with documented involvement in systematic human rights violations and human smuggling,1 EU institutions and Member States provide technical, logistical, and political support, and often even direct operational coordination. The aim is to make the scLYCG intercept migrant boats before they can reach European SAR zones, or even – as recently documented2 – within them. Interceptions carried out by the scLYCG within a European SAR zone represent a further stage of escalation.

Alarm Phone, borderline-europe, Mediterranea and Sea-Watch, activists and NGOs present at sea, have directly witnessed and documented illegal push- and pull-backs to Libya. We have observed the complete incapacity of the Libyan authorities to competently coordinate SAR events, which have resulted in a high number of fatalities. We have also witnessed the deep ties between European military and Coast Guard forces with the scLYCG in severe breach of several international laws and conventions. This report provides detailed reconstructions of three SAR events that substantiate this claim and that are emblematic of a form of EU-Libyan cooperation that has prompted the interception and return of tens of thousands of people by the scLYCG to Libyan torture camps. These reconstructions are based on our first-hand observations at sea, and they include communications with European and Libyan authorities, overheard radio communications between different authorities, and distress calls from people in distress at sea.

- In case 1 we show how the Italian MRCC repeatedly refused to take coordination responsibility for the rescue of a distress case whilst still obviously coordinating air assets to monitor the wooden boat in distress. The boat in distress was intercepted by the scLYCG more than 12 hours after authorities were alerted for the first time.

- In case 2 we demonstrate how an EUNAVFOR MED aerial asset directly coordinated with the scLYCG to intercept escaping migrants. The position of two rubber boats spotted by aerial assets was provided exclusively to the scLYCG despite the presence of NGO vessels in the area. The scLYCG were then able to intercept the migrants and return them to Libya.

- In case 3 we detail how the Italian navy ship Comandante Bettica ignored the request for urgent intervention in a distress case that involved a group of migrants who first reached out to the Alarm Phone and was then spotted by Sea-Watch’s reconnaissance aircraft Moonbird. Instead of rendering assistance, the Italian ship deployed a helicopter to assist the scLYCG to conduct a pull-back operation to Libya.

These cases could only be documented due to the presence and monitoring activities of NGOs active in the central Mediterranean and the Alarm Phone. Nonetheless, much of what goes on at sea remains unreported due to the shrinking operational space granted to NGOs and the limited information on distress cases and interceptions by authorities made available to them. The practices reported in this document can therefore be assumed to be exemplary of a more pervasive pattern of criminal and state-sanctioned behaviour by EU authorities.

There are a number of ways in which EU authorities and Member States have facilitated and even directly contributed to systematic ‘refoulement by proxy’ operations.3 As it has already been noted, through the creation of a new SAR region under the coordination of the so-called Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (scJRCC) Tripoli and the direct provision of naval assets, EU actors have delegated responsibility to the Libyan authorities and become complicit in the systematic interception and return of people seeking to escape from Libya. The cases documented in this report show in stark relief the crucial role played by EU aerial surveillance in mass interceptions off the coast of Libya, which have been expanded over recent months.4 EU aerial assets are deployed to spot migrant boats from the air and to then guide the scLYCG to the location of escaping boats. This aerial surveillance has led to the capture of tens of thousands of people and their return to the Libyan war zone. In effect, Europe is delegating its ‘dirty work’ to Libyan forces which depend on donated military assets as well as surveillance and coordination activities undertaken by EU institutions and Member States. This report provides exclusive data and an analysis of how the collaboration between the EU and the scLYCG works operationally, with a focus on the aerial coordination provided by EU assets and authorities. It also proves that if NGOs were permanently barred from operating at sea, few of the criminal practices reported here would be known.

Nancy Porsia reported about Bija’s smuggler activities in 2017 already.

Francesca Mannocchi has also reported extensively on militias involvement in the smuggling business in the Guardian and the Middle East Eye.

Demands

- The immediate revocation of the Libyan SAR region.

- An end to collaborations between EU institutions and Member States with Libyan authorities, including the scLYCG, due to their track record of human rights violations and overlapping relations with Libyan militias.

- An end to EU aerial surveillance facilitating pull-backs conducted by Libyan authorities.

- A stop to European (M)RCCs’ violation of international conventions by ignoring distress calls, delaying rescues, and coordinating pull-backs to Libya.

- The respect of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, and in particular the non-refoulement principle, also during the COVID-19 pandemic

- A commitment to human rights principles in SAR operations, including those taking place in the disputed Libyan SAR Region.

- The establishment of safe and legal routes for flight, ensuring the freedom of movement to all as a fundamental right.

How the EU came to remote control push-backs in the Central Mediterranean: A short history of EU/Italy-Libya collaborations on migration matters

Over the past five years, over 15,000 people are said to have lost their lives in the Central Mediterranean Sea alone.5 Of course, the real figure can be assumed to be significantly higher, considering the number of deaths unaccounted for. Despite this continuous mass dying at sea, EU institutions and Member States have not eased their restrictive migration and border policies that force hundreds of thousands onto such dangerous journeys across the sea. Quite the opposite is the case: The Mediterranean region has been increasingly militarised over recent years in order to ‘protect’ European borders while rescue capacities have been decreased and rescue NGOs de-legitimised and criminalised. At the same time, the EU and its Member States have sought to re-build and politically legitimise the so-called Libyan Coast Guard to orchestrate mass interception campaigns off the Libyan coast. In this way, tens of thousands of people have been forcibly returned to the inhumane detention camps in Libya, where torture, rape, extortion and other well-documented human rights violations are experienced daily.6

In 2012, Italy was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) for having transferred a group of Eritrean and Somali citizens rescued by an Italian military ship to the Libyan authorities in 2009.7 Returning rescued people back to Libya without providing them the possibility to ask for asylum and putting them at risk of life and torture was considered illegal under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and a form of prohibited collective expulsion contravening the principle of non-refoulment. The Hirsi ruling confirmed that after the first rescue operations were finished, people remained on board of an Italian military ship for many hours, and therefore fell under Italian jurisdiction. We can safely state that in response to this landmark ruling, EU institutions and Member States have developed ways to manage migration at sea by avoiding any kind of physical contact with people on the move. They have thereby contributed to the loss of many lives and the strengthening of the very questionable Libyan “authorities”. This strategy, however, does not exempt the EU and its Member States from their responsibilities, both from a juridical and a political point of view.

The externalisation of European borders is not a new phenomenon. Italy, especially, has played an important role in this process since the late 1990s and has engaged in several formal and informal diplomatic initiatives with Libya in order to control migration across the Mediterranean. Between 2000 and 2008, bilateral cooperation deepened in important respects, with a Memorandum of Intent signed in 2000 and an agreement reached in 2003 whose contents remained secret.8 An agreement on joint patrolling signed in December 2007 and implemented by the Treaty on Friendship, Partnership and Cooperation signed in August 2008, ordered the provision of six patrol boats and contributed to the deepening of police collaboration and exchange of information.9 In October 2010, the European Union signed an agreement on a migration cooperation agenda with Libya.10

With the NATO intervention in Libya in 2011 and the fall of Gaddafi, the EU could no longer rely on Libya to control its borders. In 2013, the European Union Integrated Border Management Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM Libya) was launched and was followed by EUNAVFOR MED’s Operation Sophia in 2015.11 Through these, the EU aimed to support the capacity of Libyan authorities to develop a broader border management strategy by funding and training the so-called Libyan Coast Guard.

The Italian military-humanitarian Operation Mare Nostrum, which rescued over 150.000 people between 2014 and 2015 and arrested so-called smugglers,12 was substituted by Frontex’s Operation Triton, aimed at controlling the borders rather than carrying out SAR activities like its predecessor.13 Operation Triton’s area of operations shifted northwards, was enlarged compared to Mare Nostrum’s and fewer assets were engaged, making it less likely for SAR operations to be carried out. As a response, civil society actors started to carry out SAR operations in late 2014, seeking to fill the gap created by the end of Mare Nostrum.

The trend of externalising border control continued in February 2017, when Italy and Libya reached a Memorandum of Understanding14 which set out new collaborations in the field of border protection.15 Between April and May 2017, Italy provided the Libyan navy and the scLYCG with four fast patrol vessels,16 which were followed by another ten in November 2019.17 In April 2020 the Ministry of Interior awarded a EUR 1.6 million contract for another six vessels to be provided to the “Libyan police”.18 The European Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) was also set up with a ‘North Africa’ window of funding of EUR 91.3 million,19 dedicated to supporting “Integrated Border and Migration Management” in Libya. The project’s main objectives included enhancing the operational capacity of the Libyan authorities in maritime and border surveillance, as well as assisting them in defining and declaring a Libyan SAR Region, which was declared by the Libyan authorities in June 2018. Now, with an official Libyan SAR Region, rescue operations in international waters off Libya are no longer “officially” coordinated via the ITMRC, the Italian Coast Guard’s coordination centre.

In the months preceding the declaration of the Libyan SAR zone, Italy, with the help of EU financial means, set up a basic Interagency National Coordination Centre (NCC) and MRCC, the current so-called Joint Rescue Coordination Center (scJRCC), in a joint building in Tripoli. In this building, Italian authorities conducted training, mentoring and monitoring, as well as technical assessments for a detailed creation of a fully-fledged National Coordination Centre. As part of the Italian military operation Mare Sicuro, an Italian military vessel also docked in Tripoli harbour to help and instruct the Libyan Navy and so-called Coast Guard with maritime cooperation and coordination. The MRCC and the so-called NCC are located in the same premises in order to facilitate the coordination between the different Libyan services involved in border surveillance and control.20 It is important to add that the scLYCG is not a unitary actor; its operations are indeed supported by other factions, such as the General Administration for Coastal Security (GACS) under the Ministry of Interior, whereas the so-called Libyan Coast Guard and Port Security is subordinate to the Ministry of Defence. Despite the support offered by Italy and the EU, the scJRCC has proved its inability to coordinate distress cases several times: it is neither available at all times, nor does its staff have sufficient English language skills as required by the IMO.21

In parallel to the support and training given to help boost the control of Libyan maritime and terrestrial borders, the EU has progressively pulled-back on its maritime presence and instead replaced it with increased aerial surveillance. EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia withdrew its maritime assets, leaving merely six aerial assets. As a direct consequence, fewer and fewer European state vessels are now able to intervene in cases of migrant boats in distress, de facto avoiding obligations to rescue and to bring rescued people to respective European coastal states. On the 25th of March 2020, the Council of the EU released a decision with which a new EUNAVFOR MED operation named “Irini” was launched to replace EUNAVFOR MED Operation Sophia. Its stated aim is to implement the UN arms embargo towards Libya, but also to “contribute to the capacity building and training of the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy in law enforcement tasks at sea” and “contribute to the disruption of the business model of human smuggling and trafficking networks through information gathering and patrolling by planes.”22 At the beginning of April, ECRE (European Council on Refugees and Exiles) reported that “the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell underlined that: “These ships are not patrolling the sea looking for people to be rescued”. Borrell contrasted this statement by saying that “Anyone in the sea has to be rescued. That is international law” and adding that “there is an agreement among the Member States that will participate in the mission how to proceed, where to disembark and how to share the burden”.23

Heller, Charles, and Lorenzo Pezzani. 2018. “Mare Clausum: Italy and the EU’s Undeclared Operation to Stem Migration across the Mediterranean.” London: Forensic Oceanography.

The role of Frontex

A crucial actor in the Central Mediterranean is the European Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex, which is currently engaged in a border control, surveillance and “Search and Rescue” operation called Themis. Also in this Frontex operation, a lack of transparency and accountability makes it difficult for NGOs and civil society organisations to understand the operational specificities. In fact, this agency – whose capacities and power have increasingly expanded over the last four years – systematically refuses to provide information on its activities and operations. The agency has failed to provide more than a few lines to define the method and the resources deployed in operation Themis. What is known, however, is that the operation has the primary aim to patrol the EU external border. Amongst other mentioned tasks, it also claims to be running SAR activities.24 However, as Frontex’s area of competence is strictly limited to 24 nautical miles off European coasts, Frontex ships do not intervene very often to assist migrants in distress in the Central Mediterranean.25 On the contrary, border patrolling is largely limited to surveillance activities conducted by the agency’s air assets. This is something we have witnessed through our own activities at sea and it has also been confirmed by Frontex itself,26 as stated on their website:

“to expand its ability to monitor the external borders and share the gathered information with EU Member States, Frontex has rolled out the Multipurpose Aerial Surveillance (MAS), which allows for planes monitoring the external borders to feed live video and other information directly to the Frontex headquarters and affected EU countries. The agency is also testing the use of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) for border surveillance in several countries around Europe.”27

The use of drones and planes for border patrolling in the Central Mediterranean allows Frontex to gain knowledge of the presence of boats in distress and their positions without having to engage in rescue activities. As a systematic praxis, Frontex officers engage in an illegitimate and formal interpretation of international law of the sea by alerting only the “competent” RCC according to the geographical position of the SAR event. This means that if the distress event happens to take place in the disputed Libyan SAR region, only the Libyans will be asked to intervene, even when NGO ships or other ships could help in a faster and more appropriate way. When the Libyans intervene in SAR operations it is very well known by all the EU authorities that shipwrecked people will be brought back to Libya, a place designated by many international organisations as generally unsafe (for migrants in particular) and which does not meet “the criteria for being designated as a place of safety for the purpose of disembarkation following rescue at sea”.28 This formal interpretation of the coordination procedures for rescues, as defined in the international law of the sea therefore leads, concretely, to the violation of migrants’ fundamental rights.

In March 2019, the former Director-General of the European Commission Paraskevi Michou addressed Frontex Director Fabrice Leggeri in a letter, referring to the creation of the new Libyan SAR zone and restating the geographical competence of the RCC and its corresponding SAR Region:

“the procedure outlined in your letter to communicate sightings of, as well as initial actions regarding, “distress” situations directly to the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) “responsible” for the SAR region, constitutes a procedure that is in line with the provisions of the Hamburg Convention of 1979”.29

In her letter, Michou legitimises the Libyan authorities as the “responsible” RCC. She further assures that alerting these same authorities to distress cases would conform to international regulations since they hold primary responsibility for coordinating distress cases in that area. However, the letter fails to mention that this interpretation of international law is not only restrictive and contested, but also constitutive of multiple breaches of migrants’ fundamental rights. These will be detailed in the case reconstructions and analyses below.

The practice of European actors of referring distress cases taking place in the disputed Libyan SAR region to Libyan authorities was further confirmed by the European Commission Vice-President Borrell in a parliamentary Question & Answer session. He said: “in the framework of the Eurosur Fusion Service – Multipurpose Aerial Surveillance (MAS) is performed. During the execution of MAS in the pre-frontier area (since 2017 up to 20 November 2019), when Frontex detected a distress situation in the Libyan Search and Rescue Region, the Agency provided notice in 42 cases to the neighbouring Member State Rescue Coordination Centre, to EUNAVFOR MED, as well as to Libyan authorities.”30

“Filling” the rescue vacuum via the so-called Libyan Coast Guard: mapping EU’s responsibility

As emphasised in the previous section, the EU’s withdrawal from rescue operations has coincided with the support and (re)building of a so-called Libyan Coast Guard. EU institutions and Member States (especially Italy) have consistently funded and trained the so-called Libyan Coast Guard to legitimise its abilities to carry out interceptions. This endeavour to attribute “geographical competence” to the Libyan authorities culminated with the notification to the IMO of a new Libyan SAR Region, under the competence of the so-called JRCC Tripoli. The creation of this new SAR region has contributed to the complete dissolution of the EU’s responsibilities for rescues in the Central Mediterranean and the systematic referral of distress cases to the scLYCG – effectively an unaccountable set of forces whose involvement in human rights violations and human smuggling has been documented.31 Progressively, Europe has also pulled out most of its naval assets in the region and coordinates instead, through aerial surveillance, interceptions carried out by the scLYCG. This is a systematic policy of refoulement by proxy with the scLYCG doing Europe’s dirty work. These mass interceptions then lead to people being brought back to the hellish conditions they have tried to escape from. Mass detention, torture, rape and extortion are daily and well-documented experiences in Libya. The creation of the Libyan SAR region affects rescued people even after the rescue: if NGO vessels or merchant vessels carry out rescues in the new Libyan SAR Region, disembarkation in Europe is handled as a humanitarian exception by Malta and Italy. This means for the rescued that they are made to wait several more days until they reach a place of safety.32

Since the creation of this new SAR zone, European actors have developed and expanded the communicational infrastructure and surveillance means to conduct pull-backs by proxy, carried out by the scLYCG despite the Libyan authorities having revealed themselves as incapable of coordinating SAR events in conformity with the duties of a supposedly competent JRCC. In the next section, we provide detailed case-reconstructions substantiating these claims.

Case reconstruction and legal analysis

The international regulations determining how Search and Rescue should be carried out

As will be further explained in the following legal references, every shipmaster’s duty to render assistance to ships in distress is covered under several international treaties. At the same time, states which are part of the same treaties and conventions are legally bound to coordinate SAR, which includes providing an indication of a safe place to disembark shipwrecked people.

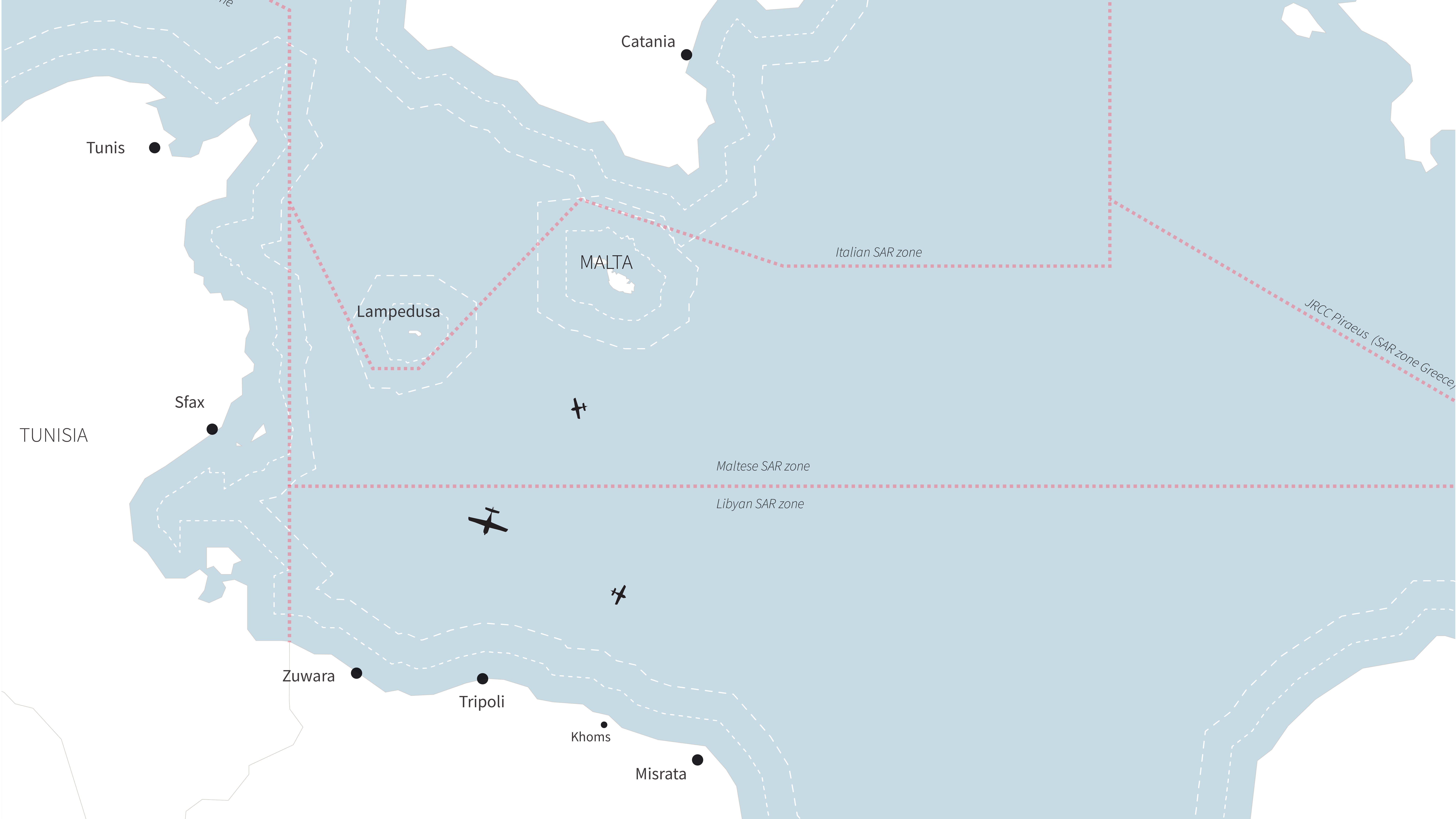

To comply with the obligation of ensuring SAR services all over the world and to avoid some sea areas lying outside zones of protection, international waters have been formally divided into different Search and Rescue Regions (SRR). The borders of these regions are defined thanks to international agreements between coastal states under the coordination of the IMO. States which declared the existence and extension of their own SRR are responsible for the coordination of SAR activities as well as for taking all necessary steps in order to protect people in danger in that area. SAR Regions include vast areas of international waters where states do not exercise sovereignty as they do in their territorial waters.

According to SAR and SOLAS conventions, states must create specific internal administrations that are in charge of receiving distress calls and coordinating rescue operations. These administrations are called Maritime Rescue Coordination Centers (MRCCs) and they can have different forms of internal organization. They must be reachable anytime by phone and officers on duty must be able to speak English. Their telephone and email contact, as well as the geographical extension of the SRR, must be published on the IMO website in order to guarantee safety of life at sea. Every state must then set up internal structures and operational plans to guarantee the fast and efficient management of distress situations.

When information of a distress case reaches an MRCC, the latter immediately falls under the obligation to intervene and take responsibility for the case, also when the event is taking place outside its SRR, until another MRCC formally assumes the responsibility. Obviously, to comply with international law of the sea and human rights laws, the following MRCC must be able to provide concrete assistance, launch and coordinate an appropriate SAR operation and provide a safe place for the survivor’s disembarkation.

The right to receive assistance in distress at sea and be disembarked in a safe harbour is not subject to any kind of discrimination or reduction based on nationality, juridical status or to the reason why a person finds themselves in danger during navigation.

The information about a distress case can be provided in different ways (phone, email, radio, satellite communication systems etc.) and it can come from different actors: passengers of the ship in distress, other ships passing close to the SAR event, reconnaissance from air assets (even drones), telephone calls from friends and relatives of people in distress at sea. These circumstances do not affect the states’ duty to provide for assistance.

The coordination of SAR activities includes a number of steps and actions. MRCCs are firstly responsible for the assessment of the level of danger in the specific distress situation and to spread the information on the presence of the case to all assets in the area in order to provide fast help. This is particularly crucial when there are no state-run ships nearby, which are able or close enough to promptly intervene – as is often the case in the Central Mediterranean.

In fact, since the creation of the actual international law system concerning the protection of life at sea, states had always relied on the intervention of private ships responding both to the long-standing principle which obliges shipmasters to render assistance to other ships in danger and on the international rules which allow MRCCs to instruct private ships during rescue operations.

When more than one MRCC is asked to intervene or is aware of the existence of a SAR event, MRCCs have the duty to coordinate between each other and provide for all the necessary guarantees both for the ship in distress and its passengers, as well as for the ship(s) carrying out the rescue operation.

Coordination of SAR activities does not end when shipwrecked people are onboard the rescue ship. SAR activities only end when the rescued people are disembarked in a place which can be considered “safe”, which means where their life, basic needs and human rights are not at risk anymore.

In concrete terms, this means that if a state cannot provide for a real safe place on its own territory there must be a prompt coordination between involved states in order to release the shipmaster of the rescue ship from their responsibilities over rescued people, as soon as possible, and at the same time guarantee for the safety of the latter until and after they reach land.

Case 1: The Italian MRCC’s hawkish approach to distress at sea

10.04.2019: Italian MRCC refuses to take coordination responsibility for a distress case for over 12 hours whilst still obviously coordinating air assets to monitor the wooden boat in distress. The scLYCG intervenes after 12 hours.

In the early morning of 10 April 2019, Alarm Phone received a call from a small group of migrants, about 20 nautical miles off the coast of Zuwara, in Libya. They informed Alarm Phone that their engine had fallen into the water and that they were in urgent need of help. They had been at sea since 22:00 CEST the night before and, according to their testimony, left Libya with 28 people on board, but 8 people had already fallen into the water and gone missing. Only 20 survivors had managed to stay on board.

Alarm Phone shift was able to retrieve their GPS position and passed it on to the civil reconnaissance aircraft Moonbird33 and to the ITMRCC. The latter would not give any confirmation of a launch of a SAR operation. Alarm Phone also informed the Tunisian Coast Guard via phone and email about the distress situation. The shift stayed in contact with the boat, and between 8:00 and 8:30 CEST, the migrants reported that they could see an airplane. Moonbird was able to arrive on scene and confirm the position given by the boat to Alarm Phone. Alarm Phone tried contacting the scLYCG but was unable to reach anyone. Meanwhile, Moonbird’s Air Liaison Officer (ALO) also called ITMRCC, and ITMRCC informed them that the scLYCG was the coordinating authority.

Once more, Alarm Phone called the scLYCG, to no avail. The Tunisian Coast Guard informed the Alarm Phone that they would coordinate with JRCC Tripoli and ITMRCC. Moonbird, on site, then decided to make a Mayday Relay34 to which the French EUNAVFOR MED aircraft Falcon 50 responded almost immediately “copy” and proceeded to the position. Moonbird then tried to contact VOS Triton, a supply vessel which was operating around the Farshah oil platform, not too far from the distress case. Moonbird then observed the Falcon 50 dropping life rafts and smoke cans onto the distress scene.35 Shortly afterwards, Moonbird had to leave the scene due to lack of fuel.

Meanwhile, from land, Moonbird’s ALO called ITMRCC which refused to take coordination responsibility, referring to the Libyans as the “competent authority” and also mentioning that the civil reconnaissance aircraft should get in contact with MRCC Tunisia. Shortly afterwards, ITMRCC sent out a NAVTEX message36 on behalf of JRCC Tripoli again reiterating that Tripoli was the coordinating authority for this SAR event.

On the boat, the situation became more tense. Alarm Phone passed on the number of the authorities to the people in distress who then called the ITMRCC themselves. By this time, it was midday and Moonbird’s ALO decided to call ITMRCC again. They passed on all relevant information to the authorities and pointed out their coordination responsibility. In another attempt to engage the commercial actors nearby the distress scene, Moonbird’s head of mission called the company Vroon owning one of the supply ships in the vicinity. The company refused to engage.

In the meantime, Alarm Phone remained in contact with the migrants, informed RCC Malta and further decided to send a summary of the information it had gathered on the case to ITMRCC and RCC Malta, requesting immediate assistance. Alarm Phone further shared that they had also passed on all the information on the case to the Libyan and Tunisian authorities as well. At 15:52 CEST the hotline received an email from MRCC Rome stating JRCC Libya would coordinate the rescue and that Rome had sent a distress alert to all ships.

Sea-Watch decided to launch a second monitoring mission with the aircraft Moonbird which took off at 15:24 CEST, to head back towards the distress case. Moonbird’s ALO was informed by ITMRCC that a Spanish EUNAVFOR MED aircraft, Cotos 45, was on scene. At 16:30 CEST Moonbird was able to locate and visualize the wooden boat again. Two life rafts were deployed but remained empty and adrift approximately one nautical mile away from the boat. Cotos 45 (ENFM) was circling nearby the area as well. Moonbird decided to head north to identify all close-by ships and to request them to assist. It spotted four merchant vessels near the Farshah oil platform: VOS TRITON, VOS APHRODITE, ASSO ZEJT 1, MELODY 5. The ASSO ZEJT 1 was the closest to the wooden boat. Unfortunately, at that point, Moonbird had to abort its mission due to engine problems and return.

At 19:40 CEST Alarm Phone could no longer reach the Thuraya number (satellite phone) of the people in distress. It appeared that the phone’s battery had run out. Alarm Phone then called RCC Malta, imploring them to reach out to the commercial vessels in the vicinity – but they refused. Finally, at 20:05 CEST, MRCC Rome informed Alarm Phone that the Libyans had found the boat and picked up the distressed, more than 12 hours after Alarm Phone first alerted authorities to the distress case.

From the reconstruction of this case, it is clear that several European air assets – the Falcon 50 and the Cotos 45 – were present on scene on the day the distress was declared. Hence, we can reasonably assume that there was coordination of the European military operation EUNAVFOR MED and the Italian MRCC, who were aware all along of this distress case and decided not to order any of the nearby commercial vessels to intervene. Instead, they delayed rescue while constantly referring civil actors requesting information to the unresponsive JRCC Tripoli. Eventually, the scLYCG was able to conduct a pull-back. We know nothing more of the fate of the people who were intercepted and returned to Libya or of those who had allegedly gone overboard.

Case 1 | Legal reference 1:

The first RCC receiving the distress call has the obligation to intervene and coordinate operations at sea, at least until coordination is formally and substantially assumed by another RCC.

In fact, RESOLUTION MSC.167(78), adopted on 20 May 2004, called “GUIDELINES ON THE TREATMENT OF PERSONS RESCUED AT SEA” in art. 6.7 provide that “The first RCC, however, is responsible for co-ordinating the case until the responsible RCC or another competent authority assumes responsibility.”

This principle is essential as it determines the certainty for each seafarer to identify the authority responsible for the rescue of human life at sea.

This obligation remains, even if the SAR event is outside the area of responsibility of the MRCC having first been notified of the distress case. The IAMSAR manual establishes that the first MRCC that receives news of a possible SAR emergency situation has the responsibility to take the first immediate actions to manage such situation, even if the event is outside its specific area of responsibility.

The coordination continues to be the responsibility of the first MRCC until it passes to another RCC, which is the one responsible for the area or another one which is in a position to provide more appropriate assistance. This means that the obligations of the first MRCC do not cease, unless it is concretely possible to transfer coordination to an RCC that can demonstrate reliability and ability to coordinate rescue.

This interpretation is also reflected in Report 7.12.2018 of the Catania Court of Ministers, which states that “under the Hamburg Convention ‘SAR’, as well as the subsequent Guidelines on the treatment of persons rescued at sea, the State of ‘first contact’ with persons in distress (in this case, Italy) has the obligation to intervene and coordinate rescue operations also outside its own SAR area, and this where the national authority which would be competent according to the distribution of maritime waters (in this case, Malta) does not intervene in good time.”

Case 1 | Legal reference 2:

As mentioned above, the duty to render assistance to people and ships in distress at sea is general and affects all types of ships, whether state (even war) ships or private ships. States, on the other hand, have to guarantee SAR services in their Search and Rescue Regions but they also have responsibilities that go beyond the extension of these regions.

In many cases, states are not able to intervene directly and in time with their own assets, but they remain bound to the duties connected to rescue at sea. In particular, they have to spread the information to all ships in the area and coordinate those who are close to the position of the SAR event and able to intervene. Art.1.3.3 of the SAR Convention defines search and rescue services as “The performance of distress monitoring, communication, coordination and search and rescue functions, including provision of medical advice, initial medical assistance, or medical evacuation, through the use of public and private resources including co-operating aircraft, vessels and other craft and installations”. The use of private resources is often necessary when state assets are not able to perform SAR activities and they are involved in the operations through the use of different satellite communication instruments (Navtex, Inmarsat-C). The information concerning the presence of ships in distress can be spread also in other ways and can arrive from different sources (via radio, via satellite phone etc.). Reg. 33 of the SOLAS Convention underlines the duties which arise from having knowledge of a distress situation: “The master of a ship at sea which is in a position to be able to provide assistance on receiving information from any source that persons are in distress at sea, is bound to proceed with all speed to their assistance, if possible informing them or the search and rescue service that the ship is doing so”. This provision simply reaffirms the duty to render assistance to people and ships in danger at sea, a basic principle which is part of several international law instruments and of the so-called jus cogens. Art. States have to coordinate assets in the area, even when they are private assets, and those assets must fulfil the obligation to do whatever is in their power to provide for help and carry out Search and Rescue operations (from the beginning to the end, which means until the moment in which rescued people can disembark in a safe place, see IMO Guidelines on the treatment of people rescued at sea, par. 6.12).

The criminal legislation of European states punishes the failure to assist and this same conduct held at sea constitutes a specific crime (i.e. art. 1113 IT naval code, section 414 Dutch Criminal Code and section 358 Commercial Code, §2(1) and §10 Verordnung über die Sicherung der Seefahrt).

Case 2: Keep the NGOs out the loop: EUNAVFOR MED and Armed Forces of Malta’s exclusive communications with the scLYCG

02.05.2019: EUNAVFOR MED air asset directly coordinates with the scLYCG. The position of two rubber boats spotted by aerial assets is exclusively provided to the scLYCG which was then able to intercept them and return the people back to Libya.

The dynamics of this event are a clear example of the ways in which European RCCs have been dealing with SAR activities for several months now. Thus, they de facto prevent people from escaping from Libya by informing only the Libyan authorities of the position of migrant boats in the Libyan SAR zone thanks to the monitoring activities of air assets mainly deployed by Frontex and EUNAVFOR MED.

On the 2 May 2019, the EU authorities were aware of at least two distress cases in the disputed Libyan SAR zone. On that date, all the passengers of the two boats were intercepted and brought back to Libya by the scLYCG with the clear support of European authorities and especially through the intervention of the EUNAVFOR MED air asset Seagull 19 and in the presence of the Maltese aircraft Beech B200 from the Armed Forces of Malta (AFM).

As confirmed by ITMRCC to Mare Jonio (the ship run by the organization Mediterranea – saving humans) later that same day, the two rubber boats were spotted by “an airborne patrol” and were “in the Libyan area of competence”.37 ITMRCC added that the above-mentioned aircrafts reported both positions to the “competent authorities” in Tripoli, who took over the coordination of rescue operations and sent a naval asset to the area. That same day, ITMRCC received several offers by Mare Jonio to reach the two boats in distress and avoid the migrants being returned to Libya by the scLYCG.

At 13:48 CEST the ALO of monitoring aircraft Colibri contacted the ITMRCC in order to find out whether there were any open SAR cases in which they could assist. Colibri was told that there were two distress cases which – according to the Italian authorities – were coordinated by the Libyans who had everything “under control”. The ITMRCC officer also confirmed to be in contact with airplanes in the area.

When Colibri arrived on scene, around 14:00 CEST, there were two air assets: the Beech B200 from the AFM and the Seagull 19, an aircraft part of the EUNAVFOR MED air fleet flying under Luxembourg flag.

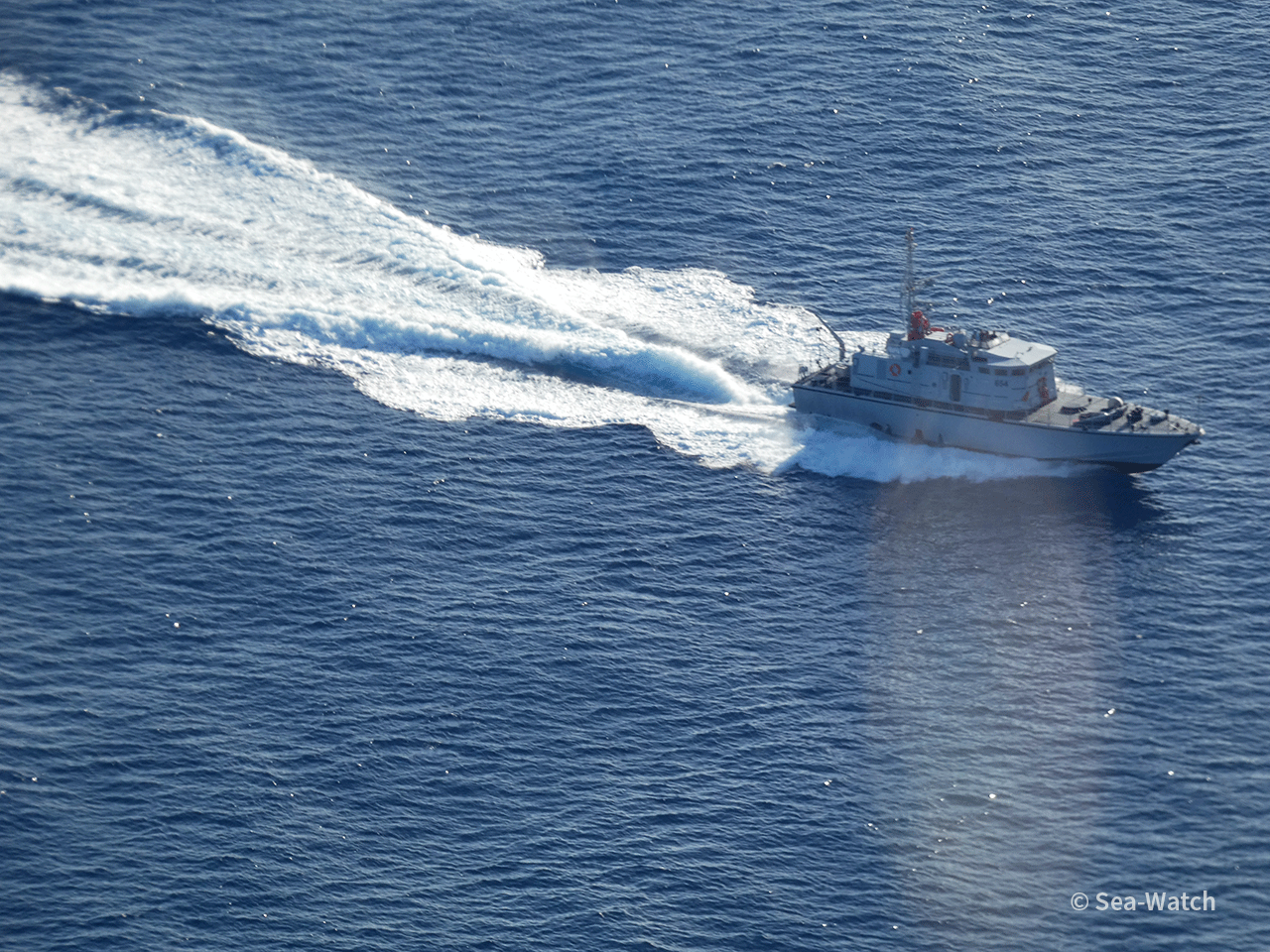

Colibri overheard that Seagull 19 was already in direct contact with the scLYCG via radio, therefore it was known that a Libyan ship – the patrol boat Sabratha 654 – was heading towards the first target, a white rubber boat carrying around 80 people trying to flee from Libya, and would have arrived almost half an hour later in the position which was initially provided by Seagull 19 via VHF.

The patrol boat Sabratha 654 was a former Italian ship (classe Bigliani) used by the Guardia di Finanza and given by Italy to the Libyan authorities in 2010. The Italian government has committed to its partial financing and maintenance ever since.

Legal commentary: The Italian Government has provided the scLYCG with radar, equipment, technical instrumentation and numerous patrol boats. The first patrol boats were the so-called Bigliani belonging to the Italian Guardia di Finanza which were given by the Italian Government to Libya in 2017.38 Subsequently, funding was allocated for the restoration of four patrol boats. Finally, in August 2018, another twelve boats were supposed to be given to the scLYCG according to the Decree Law no. 84/2018. The provision of patrol boats and other equipment strengthens the Libyan authorities who use them to conduct violent interceptions and return migrants to places of torture. The legitimacy of these financial and material support to the Libyan GNA has been challenged in front of Italian administrative courts by civil society organizations and the proceeding is still pending.39

Around 15:00 CEST the EUNAVFOR MED air asset, overseeing the scene from the air, communicated to the scLYCG the exact position of the two rubber boats, including the one Colibri was also monitoring.

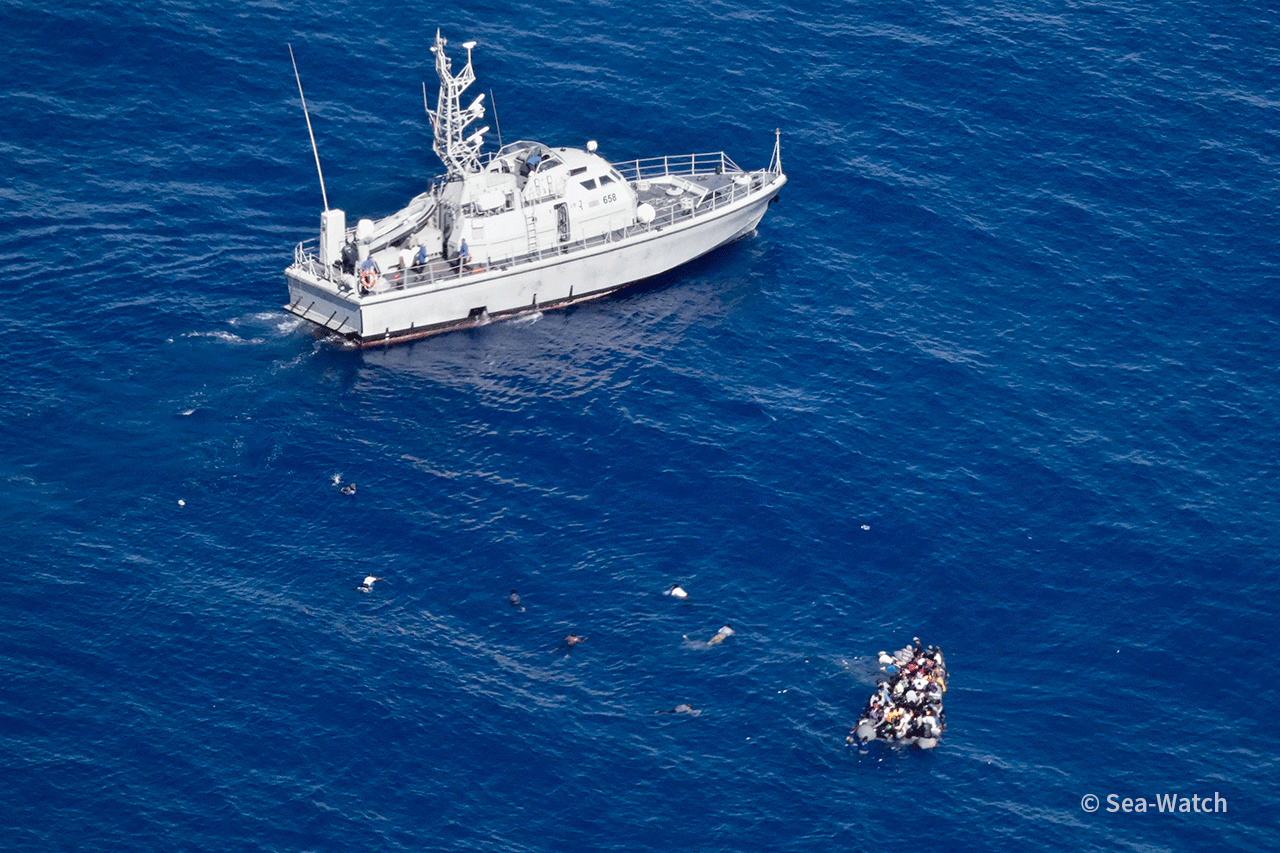

Immediately after, the Libyan patrol boat arrived on scene and started literally chasing the rubber boat, which was clearly trying to get away, most likely to avoid being pulled-back to Libya.

During the entire operation Seagull 19 flew over them, acting as on scene coordinator of the “rescue” operation, as confirmed to Colibri shortly before the interception.

| Seagull19: | Colibri, Colibri. That’s Seagull19, [on frequency] 131.9 |

| Colibri: | Am I assuming [you] correctly as On-Scene Command of this case? Over. |

| Seagull19: | More or less, yes. |

| Colibri: | To whom have you reported this target? Over. |

| Seagull19: | Colibri, unfortunately this is information I can’t tell you. |

| Colibri: | Colibri: Can you confirm to me that you are coordinating directly with Libyan Patrol Boat? Colibri. |

| Seagull19: | Affirm |

Around 16:30 CEST Seagull 19 also provided the coordinates of the second rubber boat in distress, with approximately 100 people on board, not far from the first, and Sabratha 654 then set its course towards it, as confirmed by ITMRCC.

Both ITMRCC and the Maltese RCC confirmed in the late afternoon that both rubber boats were found by the Libyan patrol boat Sabratha 654. It is thus clear that the people in distress were brought back to Libya.

Case 2 | Legal reference 1:

No one can be returned to a place where their life is not safe. Art. 33 Refugee Convention affirms that “No Contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”.

This principle concerns all the bodies of the Member States of the EU and the institutions and agencies of the EU themselves, which are obliged to behave in such a way as to prevent any person from being sent back to a place where their life is not safe. Similarly, the conduct of those who hand over – in any way – foreign citizens to the Libyan authorities exposing a person to the danger or to the violation of Article 33 (principle of non-refoulement) constitutes a violation of the non-refoulement principle. In fact, Libyan authorities, in addition to using violence in rescue and disembarkation operations, always bring migrants to places of detention where their rights are heavily violated.

The direct and exclusive call to the Libyan authorities to intervene and bring people back to Libya from EUNAVFOR MED or Frontex planes, the transfer of coordination from ITMRCC to the Libyan authorities and the transhipment of refugees from merchant or military vessels to Libyan patrol boats, expose foreign citizens to the risk of refoulement to places where their fundamental rights are not guaranteed or, worse, systematically violated. UNSMIL’s December 2018 Report on the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya entitled “Desperate and Dangerous: Report on the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya”40 shows in which degrading conditions migrants find themselves in the detention centres of the Libyan Ministry of Interior: “Many detainees in DCIM (Directorate for Combatting Illegal Migration) centres have survived horrible abuses by traffickers and are in need of specific medical and psychological care and rehabilitation. They are systematically detained in dramatic conditions, including lack of food, heavy beatings, burning with incandescent metals, electrocution, sexual abuse of women and girls, with the aim of extorting money from their families, through a complex system of money transfer, which extends to many countries”.

The ban on bringing people back to Libya, or helping the scLYCG to do so, is recognised by numerous Italian or international bodies and organizations. Among them:

- Civil Court of Rome, which in a ruling of 28.11.2019 sentenced Italy to pay damages and to grant an entry visa for access to the asylum application for 14 foreign nationals handed over by the Italian Navy to the scLYCG.41

- The Court of Assizes of Milan with the decision of 10.10.201742 and the Court of Assizes of Agrigento with the decision n. 1/201843 that condemned foreign citizens who committed unspeakable violence and abuses against other migrants in Libyan detention centers.

- The decision of the GIP (preliminary investigation judge) of Agrigento ordering the release of Carola Rackete who could not bring the migrants back to Libya, since it was not a safe port of disembarkation.44 This decision was recently confirmed by the highest court (Corte di Cassazione) which underlined that the duty to rescue does not end with the onboarding of shipwrecked people, but it necessarily entails also their disembarkation in a safe place.45

- The European Court of Human Rights that on 23.02.2012 condemned Italy in the Hirsi Jamaa and others for having transferred asylum seekers to Libyan patrol boats after having rescued them with a military vessel on the 06.05.2009.46

- The GIP of the Court of Trapani (preliminary investigation judge), which acquitted two migrants accused of leading an uprising on board for not being brought back to Libya for not committing a crime because they acted in self-defence, with a judgment of 23 May 2019.47

ASGI against MAE (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and Ministry of Interior, is currently pending in front of the Italian Council of State

more recently GLAN, ASGI and ARCI submitted a complaint before the European Court of Auditors (ECA) to request the launch of an audit of the EU’s cooperation with Libya. Such an audit would seek to determine whether the EU has breached its financial regulations, as well as its human rights obligations, in its support for Libyan border management, see: https://www.glanlaw.org/eu-complicity-in-libyan-abuses.

Case 3: Comandante Bettica turns a blind eye to Mayday Relay

23.05.2019: Italian navy ship ignores NGO’s Mayday Relay and deploys helicopter to assist so-called Libyan Coast Guard in a coordinated pull-back to the Libyan hell

On the 23rd of May 2019, shortly before 13:45 CEST Alarm Phone received a distress call from a rubber boat 40 miles in international waters, off the Libyan coast. The migrants on board said they were around 90 people and in urgent need of help. Alarm Phone passed on the gathered information, including GPS position and description of the boat, to both the Italian MRCC and civil reconnaissance aircraft Colibri. At 15:03 CEST, Colibri arrived at the position provided by Alarm Phone. It observed that the boat’s tubes were deflating and thus provided a second confirmation that the people on board were in grave danger. Colibri sent out a Mayday Relay, in order to alert all ships in the area that help was needed urgently. On the way to the scene of distress, Colibri had spotted an Italian military ship, the Comandante Bettica, stationed about 39 miles from the distress scene.48 On the phone to the ITMRCC a few minutes later, Colibri’s ALO mentioned the presence of the navy boat nearby and asked for its assistance.

| ALO: | did you copy the position, and did you copy that people are in the water the tubes are totally deflated, the boat is no longer moving and people are holding on to the tubes. Did you get that message? |

| ITMRCC: | No I didn’t receive this message, please repeat the situation. |

| ALO: | There is a rubber boat. |

| ITMRCC: | [interrupts] Yes I know this, but what is the update? |

| ALO: | Tubes are deflated [repeats messages above]. |

Colibri’s ALO provided the updated position of the boat in distress, recorded at 15:03 CEST, informed the authorities in Rome that the aircraft had sent out a Mayday Relay on behalf of this boat and added: “the next vessel in vicinity of this distress case is the Italian military vessel Comandante Bettica. They must have copied the Mayday Relay, but they are heading north east, away from the distress case.”

At 15:52 CEST, half an hour after the call was made to the ITMRCC and almost an hour after the Mayday Relay, the small aircraft circled above the military ship which also had a helicopter on board and read out the SOLAS convention to them by radio. Finally, a few minutes later, the Comandante Bettica responded, indicating to Colibri that the scLYCG were approaching and that the Comandante Bettica would assist the rescue operation with their helicopter. By this time, the rubber boat’s tubes on the left and the front had totally deflated, and its passengers were having to lift them up by themselves. Colibri implored the navy ship to launch its rapid assistance boats and not wait for the Libyans to arrive on scene to initiate the rescue. Fifteen minutes later, around 16:15 CEST, the scLYCG arrived on scene with their patrol boat Fezzan 658.49 At this point, people jumped and/or fell into the water. As far as the aircraft could observe, there were no casualties amongst the people who were in the water, but it was impossible to confirm that information.

Case 3 | Legal reference 1:

Art. 98 UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea – Montego Bay, 1982) states that “Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him”.

Masters of every type of ships, including war ships even in times of war, are therefore obliged to intervene where they come to know of a distress situation, with the support of coastal states which, from their part, have the duty to “promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements cooperate with neighbouring States for this purpose”. This is done through the establishment of Rescue Coordination Centres (RCCs) and the adoption of operational plans which are meant to guarantee the good coordination of national authorities and institutions involved in SAR operations.

The same duty is prescribed by the SOLAS Convention (Convention on the Safety of Life At Sea, 1974) in its reg. 33/V which states that “The master of a ship at sea which is in a position to be able to provide assistance on receiving information from any source that persons are in distress at sea, is bound to proceed with all speed to their assistance, if possible informing them or the search and rescue service that the ship is doing so. This obligation to provide assistance applies regardless of the nationality or status of such persons or the circumstances in which they are found”.

This means that neither the juridical status nor the reason why a person finds themselves in distress at sea can constitute a reason to avoid or delay assistance.

Italian law is also very clear concerning a master’s duty to provide assistance at sea (art. 981-982 naval code). Art. 1158 nav. code specifically states that the master of a ship who omits to provide assistance or does not try to rescue when he is obliged to intervene by this code, will be punished with detention up to two years. The law breach is punished with detention from one to six years if a personal injury derives from the omission, the sentence gets extended to three to eight years if somebody dies.

Case 3 | Legal reference 2:

The international law of the sea provides clear regulations regarding the disembarkation of people rescued at sea: par. 1.3.2 of the SAR Convention define a “rescue” as “an operation to retrieve persons in distress, provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety” and the same Convention obliges states to cooperate in order to guarantee that “survivors assisted are disembarked from the assisting ship and delivered to a place of safety, taking into account the particular circumstances of the case and guidelines developed by the Organization” (par. 3.1.9).

The instruments of international law of the sea describe the “Place of safety” (POS) as “a location where rescue operations are considered to terminate. It is also a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met. Further, it is a place from which transportation arrangements can be made for the survivors’ next or final destination” (RESOLUTION MSC.167(78) - IMO Guidelines on the treatment of people rescued at sea, par. 6.12).

Finally, a ship cannot be considered as a definitive place of safety, “even if the ship is capable of safely accommodating the survivors and may serve as a temporary place of safety, it should be relieved of this responsibility as soon as alternative arrangements can be made” (IMO Guide lines, par. 6.13). All this means that under international law of the sea, shipwrecked people must be brought in the shortest time possible to a safe place on the mainland, where their life and health are not threatened anymore.

European member states are not only legally bound to international law of the sea, they must also comply with international law on fundamental rights and asylum law. This means that when it comes to the indication of a safe place to disembark people running away from their countries or from dangerous situations (such as the Libyan one), or when a third country is instructed to intervene at sea, member states must take into consideration the consequences of these actions and the possible violations of human rights which rescued people could face because of those actions (or omissions).

EU member states are bound to the principle of non-refoulement which is a general principle of international law, provided also in several conventions and treaties (see art. 33 Geneva Convention, 1951 and arts. 2, 3 and 4 prot. 4 ECHR) which oblige States to avoid the expulsion or return of a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where their life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. Moreover, states cannot legally deny the entrance of a person in their territory when this behaviour could lead to the risk for them to suffer torture or degrading and inhuman treatments or the subsequent return to a country where they could face this risk.

European law explicitly refers to this principle in connection with SAR operations and border controls: art. 2 par. 12 of the EU reg. 656/2014 on rules for the surveillance of the external sea borders in the context of operational cooperation coordinated by Frontex defines POS as “a location where rescue operations are considered to terminate and where the survivors’ safety of life is not threatened, where their basic human needs can be met and from which transportation arrangements can be made or the survivors’ next destination or final destination, taking into account the protection of their fundamental rights in compliance with the principle of non-refoulement” and art. 3 of the Schengen Borders Code states that the regulation itself “shall apply to any person crossing the internal or external borders of Member States, without prejudice to [...] the rights of refugees and persons requesting international protection, in particular as regards non-refoulement”.

This means that an action or omission by public authorities, like MRCCs, involving the return of people to places like Libya - which is clearly not a safe place – constitutes a violation of this international law principle and hence creates a legal liability for states that have committed them.

Conclusion

As documented in this report, EU Institutions and Member States clearly aim to circumvent direct contact between the European authorities and migrants in distress in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Avoiding direct contact with migrants in distress, so they appear to believe, also means avoiding legal consequences connected to the systematic human rights violations that occur off the Libyan coast and within Libya.50 Yet, European authorities continue to play a crucial role in border enforcement practices at sea and are fully aware of migrant boats in severe distress. Through their “remote control” practices, including the spotting of boats and the coordination of interceptions from distance, they bear clear responsibility for the forced return of escaping migrants to Libya, a country at war and where human rights violations are systematically perpetrated.

From the distress cases analysed as well as the general reconstruction of EU-Libya relations proposed in this report, we can conclude the following:

- EUNAVFOR MED and Frontex planes’ spot migrant boats in distress and contact only the Libyan authorities to de facto prevent other ships from engaging and from disembarking the rescued at a safe port. This practice has resulted in both, delays in rescue operations and the return of fleeing people to Libya.51

- When informed of SAR events, the MRCCs of Italy and Malta, fail to take over the coordination of SAR operations. Instead, they wait for JRCC Tripoli to take over, despite the latter’s inability to carry out rescues adequately and to disembark the rescued in a place of safety.

- Italy has positioned a navy ship (Caprera ship and Capri ship) in the port of Tripoli that constantly cooperates with the Libyan authorities to carry out operations at sea, often directly coordinating their operations thus causing interceptions and pull-backs to a country at war

The cases we have documented in this report date from Spring 2019. However, the criminal practices we have highlighted are still ongoing. A year on, European authorities continue to monitor the Mediterranean Sea from the air and instruct their Libyan allies to capture fleeing migrants and force them back to Libya. Given Europe’s failure to render assistance and the incompetence of the scLYCG, several boats were left adrift, resulting in shipwrecks and mass fatalities.52 Over Easter 2020, the Alarm Phone documented a secret push-back operation, coordinated by RCC Malta in the Maltese SAR zone.53 Malta had been informed of the distress case for days and deployed a helicopter, seemingly, only to facilitate an interception. The people in distress were left to slowly die, whilst cargo ships passed by, and European air assets flew by. The survivors testified that the helicopter shone a red light at them and circled around them several times, before, out of the darkness, a Libyan fishing boat emerged, coming from Valletta, taking them on board and forcing them back to Libya. Five bodies were recovered, seven other people are presumed dead. All under the eyes and ears of European authorities.

Despite the European Union and its Member States’ assumption that by remotely controlling distress cases and interceptions by the scLYCG – from the air, or by avoiding direct contact with migrants – they might avoid responsibility for the rights violations these practices entail, this report proves the contrary. The policy of mass pull-backs to the Libyan war zone is a fully-fledged European policy, for which the EU and its Member States bear direct responsibility.

A report by Alarm Phone, Boderline-Europe, Mediterranea – Saving Humans and Sea-Watch, June, 17 2020